Welcome back to the Lab!

And happy fall! I don’t think I know a single person who isn’t excited for the seasonal shift; but while we hunker down with bulky sweaters and hot spiced drinks, many insects prepare for the cold weather by migrating southward.

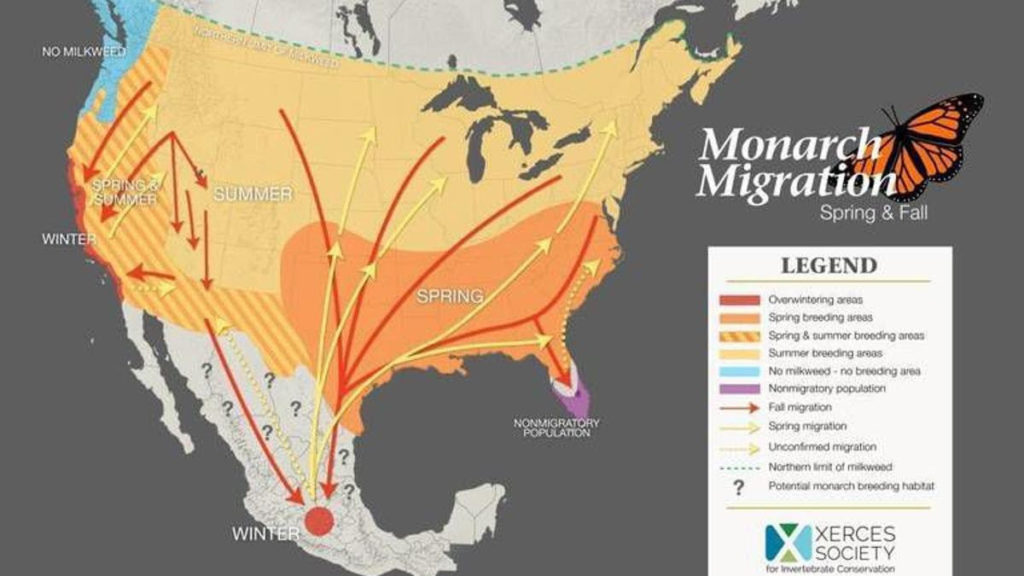

One of the most well-known insect migrations is that made by the iconic monarch. Monarchs migrate from southern Canada to central Mexico and back again, over the course of 3 generations.

Therein lies the difference between insect migration and other animal migration: because of the relatively short lifespan of most insects, the adults that make it to overwintering sites are not the adults that return to their northern breeding sites.

The monarch migration is triggered by the onset of diapause, a state of dormancy and lowered metabolic rate that many insects enter during the colder winter months, though with the monarchs, they remain active (we’ll talk about diapause in a separate issue). The butterflies store excess lipids, proteins and carbohydrates to prepare for their migration south and subsequent migration northward once diapause has ended.

Monarchs may be the icon of insect migration, but they’re not the only insects that migrate south for the winter. The painted lady butterfly, which is found in temperate regions all over the globe, makes an annual southerly migration from Britain to the Mediterranean; The Worldwide Painted Lady Migration, a citizen science project based out of the Institute of Evolutionary Biology in Barcelona, has found that some populations can travel as far as Iceland to the Sahara.

Green Darner dragonflies are a North American species whose migratory patterns are not as well studied as the monarch, but who make a similar trek each winter from northern states to Texas and Mexico. They also happen to be the official insect of Washington, my home state.

Darners are much less conspicuous than monarchs, and don’t make their migration in a large group, making them more difficult to study. In a study published only a few years ago, scientists were able to use hydrogen isotopes isolated from dragonfly wings to determine their birth ponds. Researchers were able to reveal multi-generational migration patterns in eastern populations of green darners.

Until next time, thanks for visiting the lab!

Bug Wrangler Brenna

brenna@missoulabutterflyhouse.org

Want to revisit a previous Notes from the Lab issue? Check out our archive! Do you want to request a subject for an upcoming issue? Email me at the address above and put “Notes from the Lab” in the subject line.