Birds do it. Bees do it. Bugs do it (usually). While the jury is out on whether bugs can experience emotional love, they’ve certainly come up with some interesting ways of finding a partner in this big, wide world. Bug sex, like bugs themselves, is diverse, varied, and downright weird. So, to celebrate Valentine’s Day, read on to learn the bizarre and freaky ways the bugs around you are getting it on.

My, What Bug Eyes You Have

Aquatic insects are a big deal in western Montana. Even those of us who’ve never taken advantage of our blue-ribbon trout streams (guilty as charged) have at least some knowledge of aquatic insects and their importance to stream and river health. Most of us are familiar with “the hatch,” and some have been lucky enough to witness one. Mayfly hatches are notoriously short-lived, with many species living less than 24 hours after they emerge as adults. One species, the sand-burrowing mayfly (Dolania americana), lives for a whopping five minutes before succumbing to exhaustion and drowning in the river they emerged from.

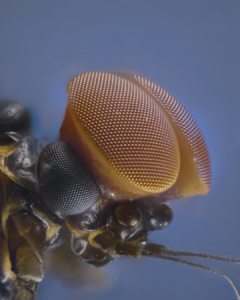

A mayfly hatch is an extraordinary event, with adults emerging from their streams en masse in a mating frenzy that excites bugs, fish, and anglers alike. But mayflies have a job to do and very little time to do it, so males have evolved a striking set of eyes to identify females in the melee. Their oversized optical organs are called turbinate eyes for their turban-like shape. During a hatch, male mayflies swarm below the females and, with their comically large eyes permanently fixed skyward, seek out a suitable female flying above. All the better to see you with, my dear.

Cheaters Gonna Cheat

Who doesn’t appreciate receiving a gift from their paramour? People do it. Penguins do it. Insects are no different. A nuptial gift is typically a coveted resource, often food, that a male presents to a female to increase his chances of mating. Occasionally, a male may produce the gift himself, as is the case with the ornate bella moth (Utetheisa ornatrix). As caterpillars, this moth feeds on plants in the Crotalaria genus, which contain poisonous alkaloid compounds that render the moth unpalatable to predators. During copulation, the male transfers his defensive alkaloids to the female, greatly improving both her and their offspring’s chemical defenses.

But occasionally, males try to cheat the system, offering substitute or false gifts to potential mates. In their paper, An Invasion of Cheats: The Evolution of Worthless Nuptial Gifts, LeBas and Hockham write, “[I]t is unknown why females require such worthless gifts as a precondition of mating.” In their study, they offer male dance flies (Rhamphomyia sulcata) nuptial tokens of varying sizes and nutritional value. They found that male flies not only exploit females by presenting them with large, albeit worthless gifts (in this case, a cotton ball, mimicking the fibrous seed tufts males will occasionally offer) but will reclaim their worthless token and re-enter the mating melee to present their gift to several more potential mates. The females, who had likely received valuable nuptial gives prior to the male’s deception, would spend several minutes trying to obtain nutritional value from the cotton ball before giving up and ending their copulatory session. While the false gift shortened the length of time spent mating, a few minutes is all the male flies need.

Traumatic Insemination

I can’t think of a clever title for this one, because this method of copulation is just as disturbing as it sounds. During these courtships, the male pierces the female’s abdomen with his aedeagus (the arthropod equivalent of a penis) and injects sperm into the wound. Insects and other arthropods have an open circulatory system, so instead of veins and arteries acting as a blood/oxygen delivery system, their internal organs are constantly swimming in hemolymph (blood). When the male injects sperm into the female’s open cavity, the sperm mixes with her hemolymph and eventually comes into contact with her reproductive organs.

Several arthropod species practice traumatic insemination, but bed bugs are the most well-studied and widely known, as it is their sole method of reproduction. Female bed bugs possess a unique organ known as a spermalege, which researchers generally agree evolved to combat the female’s risk of infection after penetration.

More Bug Love

- Male mantises can continue mating with a female even after she’s eaten his head.

- Some predatory fireflies lure other firefly species by mimicking their mating flashing patterns.

- A stick insect species holds the record for the longest sex. A captive pair of Necroscia sparaxes remained coupled for 79 days straight.

- Male cockroaches have a telescoping penis that they can maneuver to meet a female in any position – even when she’s on top.

- Damselflies form a distinctive heart shape when mating. Afterward, the male remains attached to the female, even in flight, to ensure she can lay her eggs without the interruption of another male.

- Centipedes do not copulate directly. The male presents a female with a sperm packet, which she stores in a pouch in her mouth. She then fertilizes her eggs by “licking” them.